The .io country code top-level domain (ccTLD) went through a very popular time up until 2017 with many tech-based startups eager to take advantage of the whole “input/output” connotations.

What Country is the IO domain (ccTLD)?

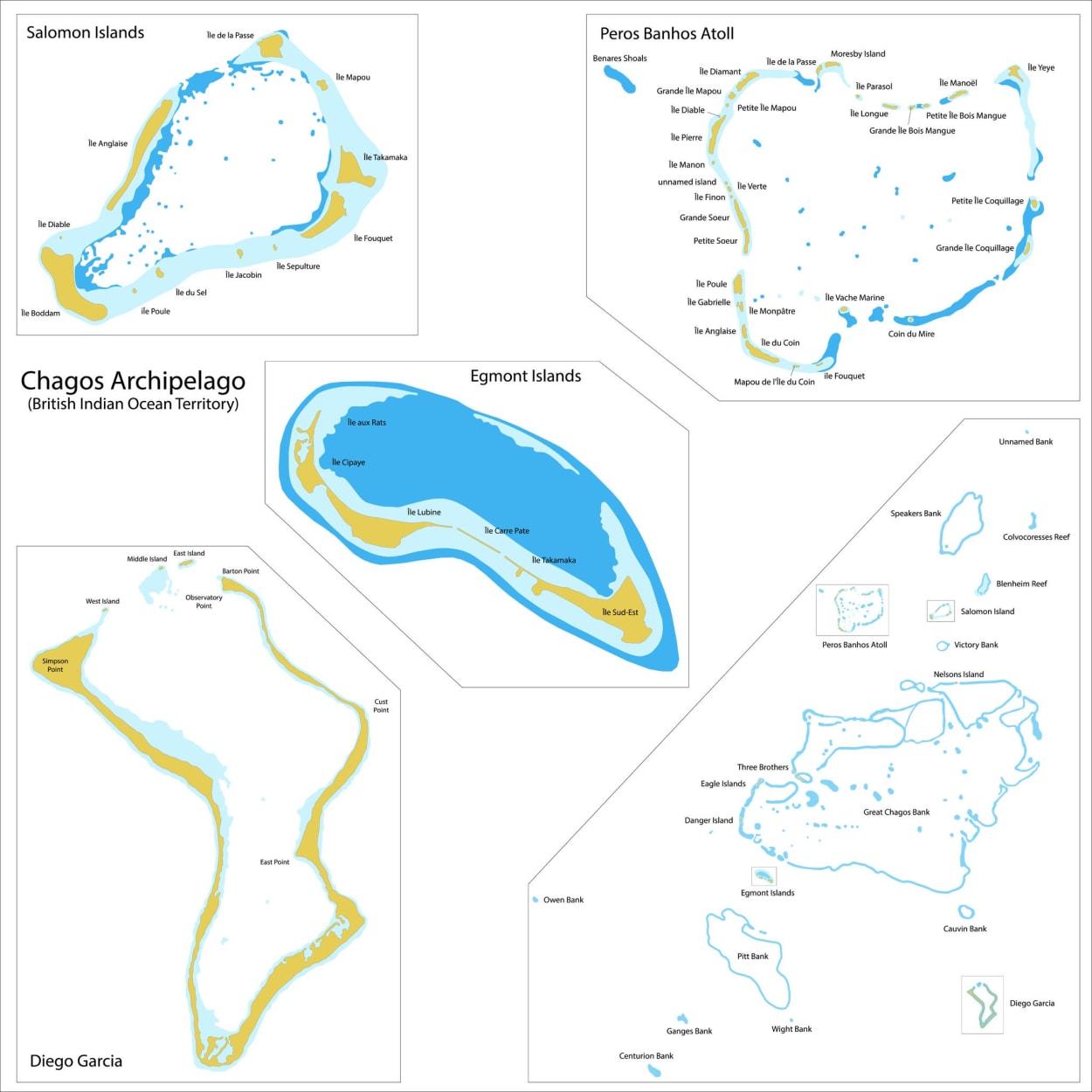

The .IO Top level domain is the country code for “Indian Ocean”. The Chagos Islands, in particular, should be the beneficial owners of the TLD.

1. The Chagossians do not benefit from the IO TLD.

Despite its popularity and the relatively high sums it generates, unlike other ccTLD’s, .io domains do not benefit the inhabitants of the Indian Ocean.

The situation for .io domains is in stark contrast to other small islands:

- .tv ccTLD — This country level domain was assigned to Tuvalu, which won independence from the United Kingdom on the 1st October 1978. Tuvalu has a population of just 10,837 as of the 2012 census. Tuvalu signed a contract with DotTV (a VeriSign Company) for $2 million US dollars a year for the use of the name, which after some signs of displeasure at the deal in 2010, was renewed in 2016 for what I imagine is a much larger sum. The point is that Tuvalu can profit from their ccTLD despite being a small country consisting of just five small islands.

- .me ccTLD — .me is an incredibly popular ccTLD, selling 320,000 domains in its first two years since going live in 2008, and now with just under 1 million as of February 2016. The .me ccTLD was assigned to Montenegro following their split from Serbia in 2006.

The previous examples are in stark contrast to the situation in Chagos. Chagos was a group of Islands inhabited by African Slaves that were brought to the islands in the 18th Century by the French. The population was further expanded when the English took over the islands in the early 19th Century with many Indian Workers joining to work on the coconut plantations.

In a quirk of fate, rather than the money received from the sale of .io ccTLDs going to the Chagossians, it goes to the government responsible for expelling them between 1968 and 1973; the United Kingdom. Although the UK Government claims they receive no money from the deal, this has been disputed by Industry Veteran Paul Kane, who now runs the .io ccTLD. Regardless of who does or does not receive the profits from the .io ccTLD, it is clear that the Chagossians DO NOT.

Depopulation of the Chagos Islands

The expulsion of the native islanders was a direct result of the Cold War. In the mid-1960s, the US was worried about a possible Soviet Expansion in the Indian Ocean and wanted to build a base in the region on an uninhabited island. The UK wanting to take advantage of an $11 million subsidy on the Polaris submarine nuclear deterrent was keen to help. After considering some alternative islands, and some political “wheeling and dealing” the Chagos Islands were targeted, which at the time was campaigning for independence from the British along with Mauritius. In return for Mauritius gaining independence, the Chagos Islands were separated from Mauritius in November 1965 by an Order in Council and renamed British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT).

A “few Tarzans or Man Fridays.”

The Chagos Islands were home to around 1800 people at the time, but to maintain the fiction that they were uninhabited (or at least only inhabited by temporary worked), they were described by Diplomat Dennis Greenhill in 1966 as follows:

The object of the exercise is to get some rocks which will remain ours; there will be no indigenous population except seagulls who have not yet got a committee. Unfortunately, along with the birds go some few Tarzans or Man Fridays whose origins are obscure and who are hopefully being wished on to Mauritius.

Another Internal Colonial Office memo read:

The Colonial Office is at present considering the line to be taken in dealing with the existing inhabitants of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). They wish to avoid using the phrase ‘permanent inhabitants’ in relation to any of the islands in the territory because to recognize that there are any permanent inhabitants will imply that there is a population whose democratic rights will have to be safeguarded and which will therefore be deemed by the UN to come within its purlieu. The solution proposed is to issue them with documents making it clear that they are ‘belongers’ of Mauritius and the Seychelles and only temporary residents of BIOT. This devise, although rather transparent, would at least give us a defensible position to take up at the UN.

Between 1967 and 1971 the depopulation of the Islands to make way for the UK \ US deal was implemented. A timeline of the depopulation was as follows:

- March 1967 — The British Government bought the Coconut Plantations from the Chagos Agalega Company under the Acquisition of Land for Public Purposes (Private Treaty) Ordinance for £660,000. The plan was to deprive the Chagossians of employment and income encouraging them to leave the Islands voluntarily.

- June 1968 — BIOT report significantly undercounted the population as just 354 to play down the scope of the depopulation. The British Governor of Mauritius, Sir Robert Scott, previously estimated the population as 1,700.

- March 1969 — Chagossians visiting Mauritius found that they could no longer catch the streamer home, with the explanation being that their contracts to work had expired. This left many homeless, jobless and without means of support. This had the effect that many family members left the islands looking for their loved ones who had not returned, but who similarly found themselves not able to return when they did so.

- March 1971 — A BIOT civil servant traveled to the Islands to tell them that they were required to leave.

- October 1971 — The remaining residents on Diego Garcia were evacuated to the Peros Banhos and Salomon Plantations.

- November 1972 — The Salomon Atoll plantation was evacuated with the population allowed to choose between Seychelles or Mauritius.

- May 1973 — The Peros Banhos Plantation was closed, and a similar choice in destination was given.

Those sent to Seychelles received severance pay, and those sent to Mauritius (a total of 426 families) received a cash settlement (although payment was not made until 1977, despite a total of £650,000 given to the Mauritian Government by the British in 1972 for this purpose).

The 1970s saw many complaints, protests and even hunger strikes about the treatment of the Islanders. In 1979, a Mauritian Committee negotiated further compensation of £4 million from the British Government in return for a signed document renouncing any claim or right of return to the Islands.

Recent Developments

There have been a number of developments since 2000, which I will summarize below, to make the point that some Islanders still dispute the loss of their Islands:

- 2000 — British High Court granted the Islanders the right to return

- June 2004 — British government made two Orders in Council under the Royal Prerogative forever banning the islanders from returning home, overriding the 2000 Court decision.

- May 2006 — British Court confirms 2004 Orders were unlawful.

- May 2007 — British Government appeal against the 2006 decision failed.

- October 2007 — British Government appealed the May 2007 decision and won.

- 2019 - More recently, in 2009, according to WikiLeaks leaked diplomatic cables, the British Government proposed that BIOT is designated as Marine Reserve to prevent former residents from returning.

- April 2010 The Marine Reserve appears to have been implemented on the 1st April 2010, and subsequently declared illegal on the 18th March 2015 under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as Mauritius had legally binding fishing rights to the waters surrounding the Islands. As a result, there is still some hope that the Islands will be eventually returned.

- 2015 - The more recent British Government has been warming to the idea of permitting the Islanders to return with resettlement studies carried out in 2015. The report confirms explicitly that there are “no fundamental legal obstacles that would prevent a resettlement of BIOT to go ahead,” with the report mainly focusing on costs, and income streams. The report, however “found there was not a clear indication of likely demand for resettlement, and costs and liabilities to the UK taxpayer were uncertain and potentially significant” dashing the hopes that the Islanders will one day return.

- June 2017 - The United Nations asked the International Court of Justice [to provide advice])(https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/06/22/un-asks-international-court-advise-britains-separation-chagos/) on the legal consequences of the United Kingdom’s separation of the Chagos islands.

- September 2018 - The ICJ hearing begins. The judgment is still awaited as of January 2019.

The .IO Registrar Deal

The rights to the .IO TLD belongs to a British Company called the Internet Computer Bureau (ICB), with Paul Kane being the Chairman and Managing Director. The company also holds the rights to several South Atlantic Islands, including Ascension (.ac), and St. Helena (.sh).

It is not clear, how or why the rights to the .IO TLD were granted to the ICB in the 1990s, but Kane did let some information slip in an interview with Gigaom:

- ICB gets to run .io “more or less indefinitely, unless we make a technical mistake.”

- Kane would not disclose the numbers of .io domains sold each year

- Kane confirmed that a fixed amount per domain goes to the “Crown Bank”, with “profits [ …] distributed to the authorities for them to operate services as they see fit,”

- The remainder is reinvested in CommunityDNS. Kane states: “We are a for-profit company that has elected to make sure that the moneys received go into infrastructure investment.”

In response to a Freedom of Information Request the Foreign and Commonwealth Office dispute these claims, they confirm that “neither the UK government nor the BIOT administration receives revenue from the sale of .io domains, which are administered independently by the ICB.”

It should be noted, however, that copies of correspondence between the Government and the ICB were withheld as it relates to commercial interests. Why they see the need to withhold documentation when no arrangements are in place seems odd, but not unusual.

It is unclear where all the money goes from the sale of the domains, but one thing is clear; It does not go to the Islanders, given that they are denied the opportunity to live there.

With the controversy surrounding the removal of the Islanders, and with attempts by the Islanders to return, this revenue is potentially critical for them. The fact they have lost their homes and a potentially significant source of revenue only pours salt into the wounds.

Sabrina Jean, the chair of the U.K. Chagos Support Association, told Gigaom:

I am afraid that this is another example of the Chagossian people being robbed — when there were tuna fishing licenses for sale the exiled Chagossians saw none of the profits, nor any of the tourist fees, nor of course the billions of pounds of rent paid by the U.S. military for leasing our homeland.

It remains to be seen what would happen to the revenue should the Islanders be allowed to resettle. It is possible, though, that a similar deal to the .tv TLD could be struck, but this is just speculation, and, in any event, unnecessary considering the findings of the report. A more limited resettlement though could prove feasible, further complicating where any revenue would go.

2. Are IO domains safe to use?

Throughout 2017 there were a number of outages of the IO domain’s DNS system, caused both by error, and by a third-party taking control of the IO’s own nameservers.

I’ll briefly go through the outages one by one, but I want to point out at the outset, that according to Domain Incite, the .IO domain was bought by Afilias around March 2017. They bought not only the domain, but the back-end infrastructure, and it is the migration of the TLDs to their own infrastructure that appears to have caused the issues. There are some reports that Afilias bought the company behind the IO domain.

I must further go on to say that while 2017 was a bad year for the reliability of the IO domain, there have been no reports of issues throughout 2018, and the beginning of 2019. I would, therefore, consider any teething problems resolved, and IO TLD’s safe to use.

- October 2016 - For several hours on October 28, 2016, only 2 out of 7 of IO domain nameservers were operational. This was confirmed by Amazon Web Services at the time as being an issue with the .io top-level domain provider.

- July 2017 - A security engineer from Google bought one of the authoritative nameservers. This enabled the engineer to gain control over every IO domain.

- September 2017 - On the 17th September 2017, two of IO domain’s authoritative nameservers were not operational. The remaining 4 nameservers were working normally, resulting in the random nature of the errors. Stream.io who first reported the error had difficulty contacting NIC.IO to resolve the issue, and concluded that “NIC.IO isn’t equipped with the technical support and systems to manage a top-level domain.”

Are IO domains good?

Moving away from the outages and controversy, there are a few benefits of using the .io TLD, including:

- Top Level Domain — Firstly, it is a Top Level Domain (TLD) which means it is great for SEO.

- Input \ Output connotations — Secondly, it has some geeky connotation with the whole " input \ output " thing, which makes it a great fit for web services or tech companies.

- Geeky — Thirdly, and I think this is the most significant reason, is that because of their high cost there is a much larger choice of domain names available.

- Interesting domain names — Another novel concept is that you can do some cool domain name hacks like “scenar.io” or “pistach.io”.

- Easy to manage — Working with the .IO TLD is just as easy as working with a .COM, NET or .ORG as it now uses the same .standardized authorization code procedure.

That being said, some people still recommend using a .com if at all possible. There is an interesting discussion on Reddit about using a .IO top level domain, over a .com. One user sums it up in this example:

For anything aimed at a general audience (whether B2C or B2C), you’ll be making your job much harder unless you use a .com address.

Sure, if your market is techies or nerds then go ahead with an obscure .io domain: but know that the rest of the world outside the tech bubble won’t understand it at all. Last year I had a client who turned down the chance to buy theperfect .com for $3k and instead went with the $50 .io. After six months of explaining to every potential customer that, no, the address isn’t whatever.io.com, they went back to the .co

I would tend to agree with this, and to some extent, the principle applies to any of the other new Top Level Domains.

Who is the Cheapest IO Domain Registrar?

Generally .io domains cost around $60 per year, about five or six times more than a traditional .com domain. They have only relatively recently ([around 2013 in the case of Namecheap](/namecheap-deals/"Namecheap reviews")) become available to the mainstream registrars.

I had a look at some of the most popular domain registrars (as at January 2019), and the price for the first year is as follows:

| Company | Price (1 year) |

|---|---|

| Namecheap | $28.88 |

| GoDaddy | $69.40 |

| Name.com | $32.99 |

Namecheap is the cheapest Registrar to buy an IO domain Registrar that I have found (even without any coupons).